Michaël Gillon, the planet hunter

1. What is (are) your current job title(s), and what does it (do they) mean?

I am Research Associate at the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (F.R.S. – FNRS). I conduct my research activities at the University of Liege, in the research group Origins in Cosmology and Astrophysics (OrCA) of the Department of Astrophysics, Geophysics and Oceanography. I am astrophysicist, and my researches focus on the detection and study of exoplanets, i.e. planets located outside the solar system.

2. Why is your job important?

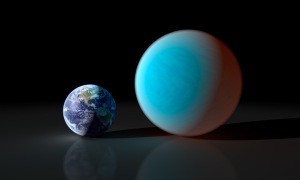

An artist’s rendition of the planet 55 Cancri e compared to Earth. Michaël Gillon led the team that used the NASA Spitzer telescope to measure the size and the temperature of this “super-Earth”. © NASA.

Our Sun is just a regular star among the hundreds of billions of stars of our Galaxy, the Milky Way. The observable Universe contains hundreds of billions of galaxies. Given these astronomical numbers, it is legitimate to wonder about the existence of other inhabited worlds up there in the sky. We are now close to a definite answer to this fundamental question. Within the last two decades, more than one thousand planets have been detected around other stars, including planets quite similar to our Earth. From this large number of exoplanet detections, two inferences of paramount importance have been drawn. First, nearly all stars harbor their own planetary systems. Secondly, at least ten percents of them have a potentially habitable planet, i.e. a terrestrial planet that could have surface conditions suitable for the emergence of life. This translates into more than 20 billion planets that could host life in the Milky Way. We are now at the edge of being able to study in detail some of these terrestrial exoplanets. This will make possible not only to compare them to their solar system counterparts, but also possibly to reveal the existence of life around another star.

In this context, I focus my research activities on the detection of terrestrial planets amenable for thorough atmospheric characterizations with existing or future instruments. Notably, I have set up an ambitious project called SPECULOOS. This typically Belgian name refers here not to delicious cookies but to the acronym “Search for PLanets EClipsing ULtra-cOOl Stars”. Based on the use of several ground-based robotic telescopes and funded by the European Research Council, SPECULOOS will search from 2016 for Earth-sized planets eclipsing the coolest and tiniest stars of the solar neighborhood. The planets that SPECULOOS will detect will be exquisite targets for atmospheric studies, including for life detection.

3. What led you to that career path?

My career path has been atypical, for the least. I have always been interested in science in general, and the possible existence of life elsewhere in particular, but I was not a very good high school student. I was more motivated by doing sport and having fun than studying. I was 17 years old when I finished high school (at the Athénée d’Aywaille), and I did not feel motivated enough for graduate studies. So I decided to join the Army. During my time of seven years as soldier in the belgian infantry, my interest for science became more and more serious. At some point, I felt motivated enough for graduate studies, and I left the Army to begin to study science at Liege University. After getting degrees in biochemistry and physics, I undertook at PhD thesis in astrophysics under the supervision of Pr Magain, still at Liege University. A significant part of my PhD was dedicated to the observation of exoplanets. After my PhD, in 2006, I got the opportunity to join as postdoctoral scientist the Geneva exoplanet group of Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz. These two astronomers are famous for having discovered the first exoplanet in 1995, and they have been working at the forefront of the field since then. I stayed at Geneva for three years, then I came back to Liege to pursue my exoplanet studies in Belgium. After a postdoc funded by the federal government, FNRS granted me permanent research position in 2010. Since then, I have been focusing my work not only on my research projects, but also on building a world-class exoplanet research team around me and on developing the field of exoplanet studies in Belgium.

4. How would you describe your typical work day?

When I am not in my office at Liege University, working with my colleagues on some exoplanet project or writing a scientific paper describing my latest results, I am often in an amazing spot like the Chilean Atacama Desert, observing the stars with a professional telescope while contemplating the gorgeous beauty of the celestial sphere. From time to time, I also attend an astronomical conference that allows exoplanet experts to meet and share their results. I like very much these conferences, especially because most of them are held in nice and sunny places!

5. What is the most exciting thing you ever had the chance to do?

I guess that you imply ‘in your job’. Then it is certainly my detection with some Geneva friends of the first eclipse of an exoplanet significantly smaller than Jupiter, in 2007. Many world class teams were competing to be the first to achieve this detection with big professional telescopes, including space-based ones. On our side, we were just having fun trying with an amateur telescope located in the Swiss Alps. Against all odds, we were the first to succeed. We could not believe it, until we confirmed our detection with bigger professional telescopes. This is the perfect illustration of one of the reasons for which I love astronomy: you can make breakthrough discoveries while having fun, without taking one-self too seriously!

6. What advice would you give to your young self?

Believe in your dreams and in yourself. And always try to use your full potential in all your enterprises! Being a scientist, i.e. being paid to study the mysteries of Nature, is one of the greatest possible jobs, so spare no effort to reach this goal if this is the dream of your life!

Michaël Gillon posing in front of TRAPPIST, a Belgian robotic telescope installed by himself and his Liege colleagues in 2010 in the Chilean Atacama Desert. TRAPPIST is dedicated to the study of planetary systems. For more information, see http://www.ati.ulg.ac.be/TRAPPIST